Kushida Shrine

Kushida-san / General Information

Kushida Shrine, considered a “power spot,” is the head shrine of Hakata’s guardian deity and boasts a history of over 1,250 years. Locally, it is affectionately called “O-Kushida-San.” The shrine was destroyed by fire during the civil wars of the Sengoku period but was later rebuilt by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who funded its reconstruction to help revitalize Hakata. Although the shrine may appear modest in size at first glance, visitors often find it more expansive and impressive than expected as they explore the grounds.

More about Shinto Shrine , Click here.

Three Gods and their Powers of Answering Prayers

This shrine enshrines three deities, each in their own dedicated hall. This separate enshrinement reflects the deep reverence the local people of Hakata have for these gods, each of whom plays a distinct role in the city’s famous festivals.

The left altar is dedicated to Amaterasu Oomikami, the sun goddess honored for ensuring a bountiful harvest. She is the focus of the Hakata Okunchi Festival on October 23rd and 24th. “Okunchi” (literally “ninth day”) traditionally marks the start of the new autumn season and is a time for rituals praying for a good harvest.

The central altar is dedicated to Oohatanushino Mikoto, the god who dispels evil. He is associated with the Hakata Setsubun Festival in February, which marks the traditional end of winter and the beginning of spring.

The right altar is dedicated to Susanoo-no-Mikoto, the god who wards off calamities. He is celebrated during the nationally renowned Hakata Gion Yamagasa Festival, held from July 1st to 15th.

Chinese Zodiac

Look up at the ceiling of the main gate. You will see the twelve zodiac signs positioned around a central needle pointing toward the year’s luckiest direction. This is the Eho, the auspicious direction you should face when eating the traditional Eho-maki sushi roll on Setsubun day. It is a unique feature to have this celestial compass displayed overhead, a fascinating detail that few visitors notice as they pass beneath it.

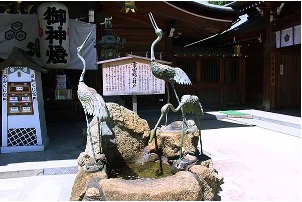

Salty Water

Water springs from beneath the main pavilion, but it is now salty seawater, indicating that this area was once surrounded by the sea. This water was once revered as “water of longevity,” believed to have health benefits for those who drank it. However, it is no longer safe for consumption.

Akachonbeeee Wind God and Thunder God

The figure on the left represents the Raijin (Thunder God), who is depicted playfully attempting to assault Hakata with wind and rain.

In response, the Fujin (Wind God) on the right is making an Akachokobe. This term from the Hakata dialect refers to the classic mocking gesture—pulling down an eyelid and sticking out the tongue—which is akin to blowing a raspberry.

While statues of the Wind and Thunder Gods are common at Shinto shrines, this pair stands out for its unique humor. Their playful interaction perfectly captures the witty and humorous character of the Hakata people.

Yamagasa Float

Of all Hakata’s festivals, the Yamagasa Festival is undoubtedly the most famous. From July 1st to 15th, magnificent floats are displayed across the city, often illuminated late into the night.

Kushida Shrine serves as the heart of the festival, being the central venue for the thrilling Oiyama race. In fact, it is impossible to speak of the Yamagasa without mentioning Kushida Shrine, which highlights the vital role shrines play in connecting with and uniting the local community.

Hakata Walls

To help revitalize Hakata after it was devastated by war, Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered the construction of a defensive wall using stones and roof tiles collected from the scorched fields.

This section of the Hakata Bei (wall) was relocated from the property of Torii Muneshiro, one of Hakata’s three major merchants. The use of such materials—likely necessitated by a shortage of proper building stone—reflects the urgent determination to restore Hakata by any means available.

Yamagasa Festival

English Official Web Site: Hakata Gion Yamagasa https://www-hakatayamakasa-com.translate.goog/?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=ja&_x_tr_pto=nu

The Hakata Gion Yamakasa is a Shinto ritual and festival held each July, centered around Kushida Shrine. From July 1st to 15th, the city is immersed in festivities, which begin with ceremonies to enshrine deities in the floats.

The core participants belong to seven districts, known as Nagare: Ebisu, Daikoku, Doi, Higashi, Nakasu, Nishi, and Chiyo. The festival is both a solemn religious event and a fierce competition for these communities.

The competition involves two types of floats, collectively called Yamakasa:

Kaki-yama: These are the one-ton, roughly 3-meter-high running floats used in the climactic race. On the final day, July 15th, the seven Nagare teams compete to carry their Kaki-yama on a five-kilometer race through Hakata, a thrilling test of speed and endurance. The starting order for the teams rotates annually among the Nagare.

Kazari-yama: These are massive, stationary floats, standing 10-15 meters high. Decorated with elaborate Hakata dolls depicting historical or pop-culture themes, they are displayed at over ten locations around Fukuoka City for the duration of the festival.

Kushidairi refers to the dedication ceremonies held in the special circular venue called the “Seidou” on July 12th and 15th for the Yamakasa Festival. In the center of this arena, surrounded by spectator stands, is a flagpole. Each float begins its run with the signal of a large drum, circles the flagpole, and then departs from the shrine grounds.

The main Oiyama race commences at 4:59 a.m. on July 15th. At the sound of the drum, the Oiyama floats enter Kushida Shrine one by one and embark on the 5-kilometer course through the streets of Hakata, finishing in Suzaki Town. Two separate times are recorded: one for the run within the Kushidairi arena and another for the longer street course.

After all the Oiyama floats have completed the race, a Noh performance called Shizume Noh is held on the Noh stage at Kushida Shrine. This ritual serves to calm the deities who have been excited by the fervor of the festival.

Other Temples in the Old District of Hakata

Hakata and Fukuoka

It is generally thought that Hakata is another name for Fukuoka, but originally, they were two different, adjacent towns. Hakata was a commercial town that prospered as a trading port from the Middle Ages, while Fukuoka was a castle town granted to the first Kuroda lord, Nagamasa, as a reward for his contribution to the victory at the Battle of Sekigahara. In the Meiji era, when the two towns were united, there was a dispute over the name. Ultimately, Fukuoka was chosen, but some places, like Hakata Station, retain the old name. Hakata and Fukuoka are separated on their west and east sides by a river, over which Nagamasa built bridges. The island in the dividing river is the origin of Nakasu, which means “Central River Island.”

During the Sengoku period (from the 15th to the 17th century), the town of Hakata was burned down several times in battles and was ultimately devastated. It was reconstructed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the preeminent samurai, after he subdued the Kyushu region in 1587. He devised a rehabilitation plan for Hakata and executed it, dividing the town into new units (Taiko-wari). For this division, a grid of streets, resembling a Go board, was laid out, using the midpoint between the two rivers as the north-south centerline. As a result, many Hakata merchants who had fled during the conflicts returned, and the town regained its vitality.

Hakata was originally situated on two separate sand dunes protruding into the sea (around the 9th century), which were later connected (in the 12th century). The north-south centerline was established by connecting the two highest points, which had been the tops of the respective dunes..

Ryuguji Temple

Ryuguji Temple, of the Jodo sect, was originally located on the beach near the port. According to legend, a mermaid was caught in Hakata Bay in 1222 and presented to the temple as a good omen. The temple was subsequently renamed Ryuguji—a reference to the legendary undersea palace of the dragon king where mermaids were said to live—and the mermaid’s remains were buried on the temple grounds.

Syofukuji Temple

Syofukuhi is the first temple of zen-Buddhism in Japan. The founder, the great master Eisai learned zen teachings in South China and found the temple here to spread the teachings in 1195. On the front gate is the flat flame with a phrase hand-written by the Gotoba Tenno Emperor. The master Eisai introduced the custom of tea drinking to Japan. By then in China, tea was drunk by the Chinese people, especially Buddhist monks who were severely trained. They thought tea was good for strengthening their body.

Gentian Temple

Genjuan Temple was founded by the Buddhist priest Mugen Genkai in 1336. The original temple was located in what is now Maedashi in Fukuoka City’s East Ward, but it was destroyed by fires during the battles that occurred between 1573 and 1591. The temple was rebuilt at its present location in 1646 by Oga Sohoku, the son of a prominent Hakata merchant. Their graves are located in the temple cemetery. Master Sengai of Shofukuji Temple spent his quiet retirement years in a hermitage named “Kohakuin” located here.

Hongakuji Temple

Hongakuji Temple (本岳寺) originally belonged to a Zen sect and was known under the kanji 本覚寺. However, at the end of the 15th century, the head priest was forced to change its affiliation to the Nichiren sect. According to the story, the priest, an avid Go player, wagered the temple in a game against the master Nichiren monk Nichiin, who had come to Hakata from Kyoto. After losing the match, he ceded the temple. As far as we know, Hongakuji is the only temple in Hakata to have changed sects.

Myotenji Temple

Myotenji Temple was originally a Nichiren sect temple founded in what is now Yanagawa in 1381. After being relocated, it later became the family temple for the Tachibana family within the Kuroda clan. In the early 17th century, a religious debate was held at the temple between its head priest, Nichichu, and a Christian missionary. Nichichu won the debate, and to commemorate his victory, a new temple was built in what is now Fukuoka’s Central Ward. It was named Shoritsuji (勝利寺), with the characters ‘Shou’ (勝) meaning ‘victory’ and ‘ritsu’ (立) meaning ‘to establish’.

Nureginu-Zuka

The “Nureginu-zuka” is a monument commemorating a tragic tale from which the phrase ‘Nureginu’ (wet kimono) originated, now used to mean a ‘false accusation.’

According to the story, a beautiful girl incurred the jealousy of her stepmother. To eliminate her, the stepmother conspired with a fisherman to falsely accuse the daughter of theft. When the girl’s father, the provincial governor of Chikuzen, heard the accusation, he decided to investigate. He checked on his daughter while she was sleeping and discovered a wet kimono placed near her—planted evidence meant to implicate her. Despite the girl’s desperate protests of innocence, the governor, believing the false proof, tragically killed his own daughter.

Later, the daughter appeared in her father’s dream, continuing to plead her innocence. He then realized his terrible mistake. To atone for his error and appease her tormented soul, he built seven stone monuments, or ‘Ishizuka.’ The nearby Ishido Bridge is said to be named after these stone mounds, as “Ishido” (石堂) is a reading that can mean “stone hall” or “stone mound,” deriving from ‘Ishizuka’ (石塚).

Kaigenji Temple

Kaigenji is a Jodo-sect temple founded in 1396. Its precincts include two sacred halls: ‘Enma-dou’ and ‘Kannon-dou’ (the latter rebuilt in 2016). The Enma-dou hall houses statues of Enma-Daio, the king of the underworld, and Datueba, an old woman who strips the dead of their clothing at the banks of the Sanzu River (the Buddhist equivalent of the Styx).

During the biannual Enma Festival, visitors offer konjac to the statue of Datueba to pray for relief from illness. This practice is linked to the preparation of konjac itself, which must be purged of its harsh, bitter impurities—a process described in Japanese as “aku o toru” (アクを取る), meaning “to remove the undesirable elements.” The word “aku” (悪) can also mean “evil” or “suffering,” creating a symbolic parallel where offering the purified food represents the prayer to remove one’s ailments. Because of this tradition, Datueba is affectionately known as ‘Konnyaku-Basan,’ or ‘the Konjac Old Lady.’

Senchakuji Temple

Senchakuji is a Jodo-sect temple founded in the mid-16th century. The name “Senchaku,” which is uncommon today, means “to eliminate the bad and choose the good.” During the Edo period, a red-light district was situated near the temple, and it became the burial site for approximately 580 prostitutes who died as Muenbotoke—deceased persons with no relatives to care for their graves or perform memorial rites.

Honkoji Temple

Honkoji Temple is a Nichiren sect temple that enshrines Daikokuten, the God of Wealth and Prosperity. The temple’s connection to this deity stems from a dramatic incident in the late 16th century. The wealthy Hakata merchant Sotatsu Kamiya was attending a tea ceremony hosted by Oda Nobunaga and was consequently caught up in the Honnoji Incident. However, according to tradition, Daikokuten appeared to him in a dream and warned him to depart immediately. Heeding this divine advice, Kamiya escaped and returned safely to Hakata. In gratitude for his salvation, he donated a statue of Daikokuten to the temple.

One Thousand Year Gate

This recently built monumental gate stands at the entrance to Hakata’s temple district. It is a reconstruction of the original Edo-period gate that welcomed travelers to Hakata on the main route from Dazaifu.